A deep dive:

The Story Behind

Calling out to You

What do you get when you mix Bach’s counterpoint with a fresh, modern neoclassical twist? That’s exactly what I set out to discover in this experiment. Let’s dive in!

What do you get when you mix Bach’s counterpoint with a fresh, modern neoclassical twist? That’s exactly what I set out to discover in this experiment. Let’s dive in!

Calling out to you lends it’s name from Bach’s Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ. I took on the challenge of combining Bach’s intricate three- and four-part writing styles and embedding them in a neoclassical framework. You’ll hear clear references to Ich ruf zu dir—I borrowed a phrase and used ornamentation typical of Baroque style, like grace notes. The tricky part was balancing the counterpoint with the more emotionally driven simplicity of neoclassical music. It’s a mix of head and heart—a playful experiment of structured contrapuntal writing against more flowing broken chords and accessible melodies. Ironically, it blends neoclassicism with the classical era, which it actually tries to escape from. But hey, rules are there to be broken!

Originally written as a chorale hymn for the organ in 1732, Ich ruf zu dir (translated as “I Call to Thee, Lord Jesus Christ”) carries a desperate, yet hopeful plea. The text by Johannes Agricola, written in 1529, asks for guidance and mercy in troubled times. Bach’s musical interpretation captures this emotion. The piano transcription by Ferruccio Busoni added a new dimension to the piece, translating it beautifully from organ to piano. From the first time I heard it, I was mesmerized, and to this day, it’s still one of those pieces that can make me stop everything and just listen.

“I think it’s fascinating how our past influences our creative output, even if we’re not aware of it at the time.”

The harmonic and melodic progression of the first few bars of the verse —the more “neoclassical” section—I wrote in a heartbeat. Reflecting on it, I suspect it might have been influenced by a hymn from my childhood, called ‘Daar waar liefde is’. Growing up, I was that kid that was dragged to church by my parents. While the sermons never really grabbed me, the choir’s multilayered music did. This one hymn in particular stuck with me. It’s funny how it might be that those early musical memories find their way back into your work without you even realizing it. I think it’s fascinating how our past influences our creative output, even if we’re not aware of it at the time.

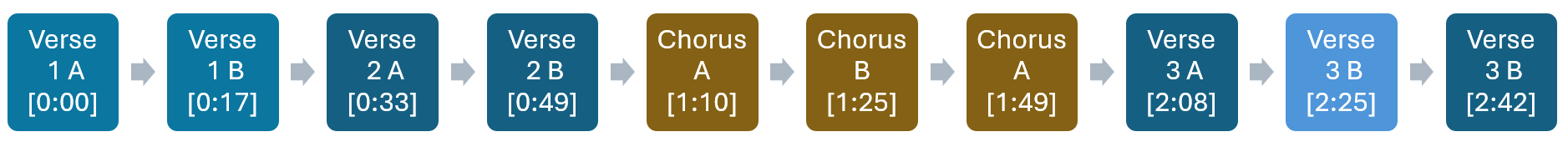

The first verse is fairly simple: just a melody over broken chords. But in the second verse [starting at 0:33], I push the melody an octave higher to make space for a second line around 0:50. This secondary line serves two purposes: to build up the dynamic within the piece and, by using counterpoint, transition into the Bach-inspired chorus. The second line works in the gaps of the melody, descending in contrast to the rising main theme, offering a subtle but deliberate shift toward the more Bach-like texture of the upcoming section.

The chorus begins at 1:10, structured in an A-B-A format. My goal was to emulate the writing style of Ich ruf zu dir, where the bass and soprano follow simple, stable lines, while the tenor weaves a more active, melodically driven part, always aware of counterpoint rules. At 1:18, I introduce an imitation of the chorus theme, but with a twist—it starts from a new harmonic point of departure. By 1:26, we reach the B section, where the soprano builds tension by climbing higher, culminating in a dissonant b9 note. Meanwhile, the middle voices create friction on downbeats, only to resolve on the weaker beats.

At 1:49, we return to the A section, this time fuller and more robust. The lines are almost identical, but now the octave doublings and the tenor line are thickened with decimes, giving the section a richer, more choral feel. You could even call it a tenor-and-alto combination.

Starting at 2:08, the verse returns, but this time with an echo of the melody an octave higher. At 2:25, the second part of the verse is played two octaves higher in a more stripped-down form, letting the individual movements of the three voices shine through. The next repetition contains a subtle nod to another Bach masterpiece—Variation 25 from the Goldberg Variations, BWV 988. Often described as the emotional pinnacle of the work, Variation 25 holds a special place in my heart. It’s sometimes called the “black pearl,” a piece of music so deeply melancholic that it feels like a musical meditation on sorrow. I remember my teacher at the conservatory describing its descending lines as “falling tears.” This imagery stayed with me, and I couldn’t help but think of it again during the passage starting at 2:42 in Calling Out to You, which features similarly descending lines.

When it came to mixing and mastering, I aimed for a sound that evokes the space of a large, echoing church. Lots of reverb and just a hint of delay created that expansive feel. At the same time, I wanted the mechanical aspects of the piano—the felt hammers and the inner workings—to be audible, creating a contrast between the spacious reverb and the intimate, tactile elements of the instrument. That said, I struggled a bit with getting the volume right, and I think I was a bit too heavy-handed with the compressor. There’s definitely room for growth on that front. Next time, I might reach out for some guidance on mastering to get it just right.

I’m curious what you think!

Leave a reply down below and let me know!

Thanks for reading!

Share your email with me, and I’ll keep you updated with new content—no more than four emails a year!