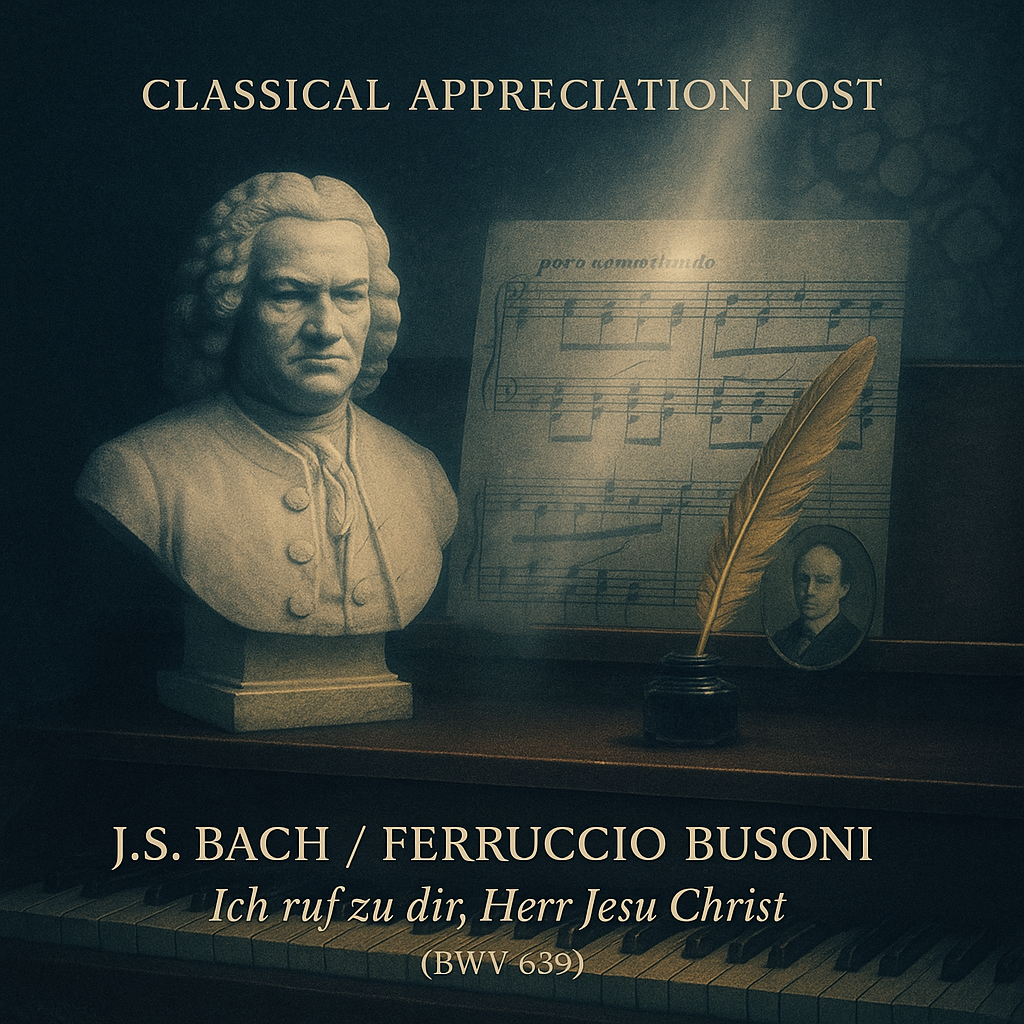

Classical Appreciation Post

Bach - Busoni: Ich ruf zu dir

At the conservatory, I had weekly lessons with my main teacher, focused on jazz. It was called ‘hoofdvak’—my principal subject. We explored the genre in depth: playing through different pieces, working on accompaniment styles, voicings, and all the ins and outs of the piano.

Alongside that, to develop proper piano technique (which I really needed), I also had classical lessons every week—my so-called ‘bijvak’. These focused on posture, finger placement, hand position, and control. But above all, I got to play beautiful classical works.

Some of those pieces—and eventually some new ones too—I’m hoping to (re)learn and bring back into my hands.